The Rise and Fall Of Yankee Rowe

In 1954, Congress passed the Atomic Energy Act opening up nuclear power to private companies. A consortium of New England utilities reacted quickly, and in the same year formed the Yankee Atomic Electric Company (YAEC). YAEC decided to build an ``experimental" plant to learn about nuclear, near the the western Massachusetts town of Rowe. They opted for a 134 MW plant, which was upgraded to 186 MW in 1963.

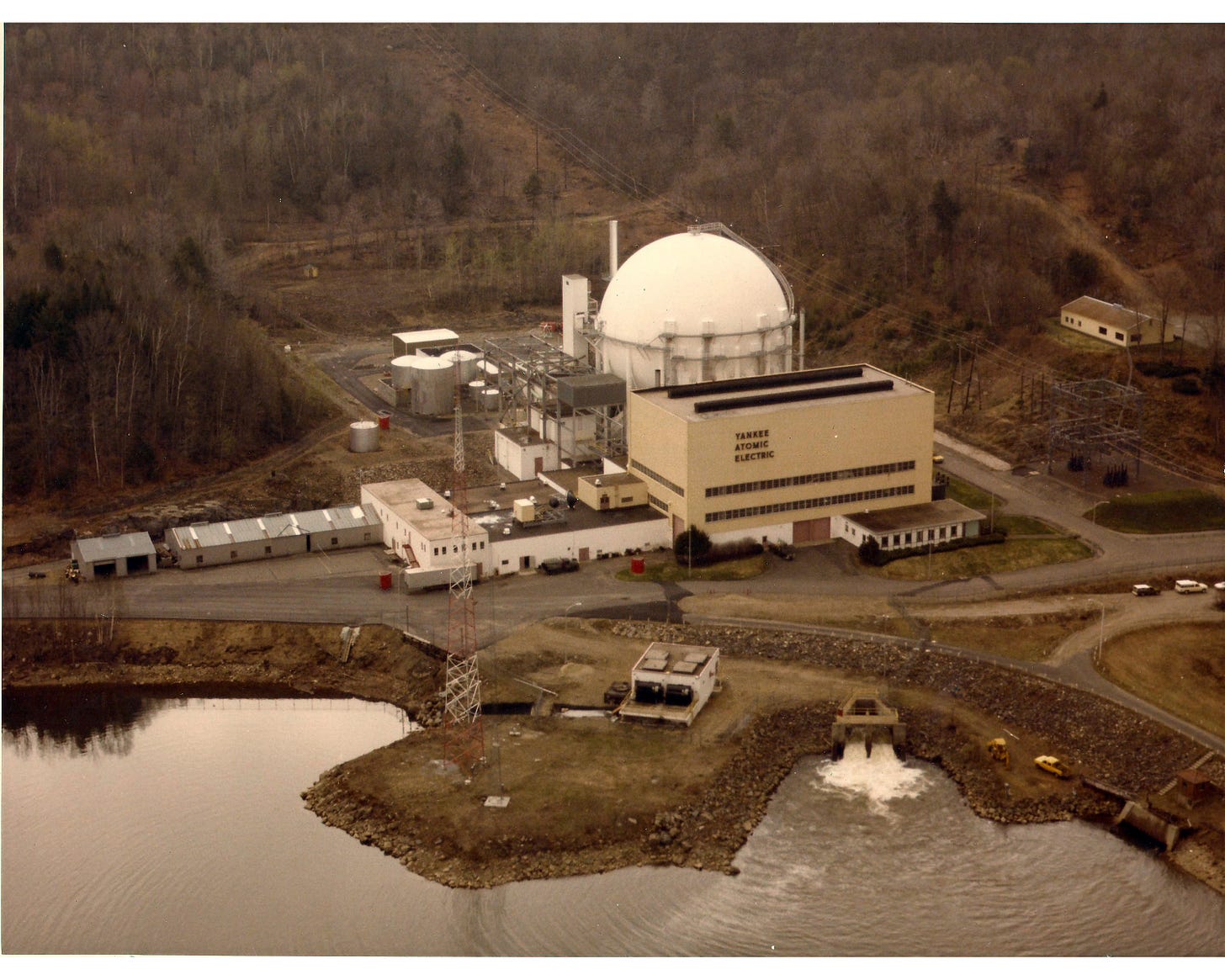

Yankee Rowe had a distinctive spherical containment rated to 35 psi, Figure 1.

Figure 1. Yankee Rowe: Reactor Cup Left, Containment Sphere Right.

The plant was located on a scenic spot on the Deerfield River, Figure 2.

Figure 2. The Little Plant that Could, 1% of New England's electricity.

Leading the project was General Kenneth Nichols, who had been deputy to General Groves on the Manhattan Project. Nichols claimed he could bring the project in for 57 million dollars. When Rickover heard this number, he was aghast. Rickover's 80 MW Shippingport had just cost 72.5 million, four times as much on a per kilowatt basis. He called Nichols and told him that cost ``is impossible to achieve ... I hate to see you ruin your reputation." Nichols did not back down. He told Rickover he was using standard off the shelf utility components and he had fixed prices for most of them. Construction started in February, 1958. The plant was connected to the grid 33 months later. The actual cost was 45 million dollars, 21% below Nichols’ budget.

During the next 32 years, Yankee Rowe generated 34 billion kilowatt-hours. By all the metrics by which the NRC rates plants, Yankee Rowe was near the top. At 5% real interest rate, the unit capital cost was 2.8 mills per kWh. The utilities had not expected to make money on this badly undersized plant; but with the explosion of fossil fuel costs in the 1970's, Rowe became a little gold mine.

But then the NRC went to work. Here's Leonard Laffond, who started as a janitor at Rowe and worked his way up to Senior Reactor Operator.

When it opened, there were 65 of us working. And when the plant closed, there were 265 of us, because of all the regulations and testing that had to be done. ... One new requirement after TMI was the plant had to have its own six million dollar simulator. Before that, you would have them train on simulators in Chicago.

Yankee Rowe's 40 year operating licence would run out in 2000. In 1990, YAEC made the mistake of starting the process for a 20 year extension. This attracted the ire of the Union of Concerned Scientists. UCS claimed that embrittlement of the Reactor Pressure Vessel made the reactor unsafe to operate, and petitioned for an immediate shutdown. The issue was could the reactor take the fast cooldown associated with a small break loss of coolant (aka LOCA) without cracking? We've had maybe two small break LOCA's (TMI was one) in about 20,000 reactor years.

Nichols had installed test specimens with the intention of periodically removing a specimen to check on the condition of the steel. But they had been poorly mounted, and had been removed in 1965 as an unnecessary nuisance. Yankee Rowe could not document the condition of the steel. The NRC decreed YAEC must prove its case or shut down in 1992, 8 years early. YAEC told the NRC they were prepared to spend $28 million to address the issues; but they needed assurance that, if the answers came out right, they would be allowed to restart. By this time, the case had become a media circus. The NRC responded with a list of additional questions.

With the economics whittled away by regulation, and with the goalposts moving every meeting, the utilities decided not to fight this infringement of the license. YAEC President Kadak diplomatically explained ``the technical criteria we must meet and the path we must follow to restart the plant are not sufficiently defined to justify spending that amount of money". First rule of US nuclear: never, ever say anything bad about the NRC.

The locals, including the fully unionized workforce, the people the UCS was saving, were stunned and then livid. They lost a 12.6 million dollar annual payroll, and another 3.8 million in local taxes and expenditures, to avoid a 0.01% chance per year small break LOCA combined with an unlikely reactor pressure vessel fracture, at which point they would be facing a TMI-like release, which would likely result in no detectable harm to the public. The little towns around Rowe withered away. The schools were particularly hard hit. Back in Boston, the UCS celebrated their victory with a nice wine and some good cheese.

Subsequent tests in Europe that attempted to duplicate the temperatures and flux facing the Rowe pressure vessel indicated that the steel still had plenty of ductility to handle the cooldown.

The brilliant start of Yankee Rowe showed what was possible. Nichols got to build Yankee Rowe before the AEC regulatory apparat was organized. Without an AEC/NRC, Yankee Rowe's construction and operation history could have been improved and duplicated over and over again at a larger scale. But we have an AEC/NRC. Within a couple of years, nothing like Yankee Rowe could be replicated. And eventually the regulatory alaraconda found a way to constrict the life out of even the cheapest of plants. In the end Rickover won; Nichols lost.

The history of Yankee Rowe encapsulates the promise and the tragedy of US nuclear power.

Just saw a great quote from comedian Jack Sitch. ‘Stupidity is scalable’ . That encapsulates this type of over regulation.

Those numbers seem to come from "The Road to Trinity" pages 342-344 (pulled from Wikipedia). Looking at the book, it seems that these numbers for cost are not adjusted by inflation. Adjusted for inflation since 1960 the capital cost would've been $450M, costing ~$3.25/We, which is still pretty damn good, a bit worse than South Korea can build the APR-1400 for today, and not bad at all for a FOAK reactor.

The book also references the Connecticut Yankee plant which was to cost $100M for 582MWe. Assuming it, too was not adjusted for inflation from the 1960 point of view they were discussing it from that'd be ~$1B today for $1.71/We, but since the plant began construction in 1964, and wasn't put online until 1968, it may actually have been as low as $1.34/We. All of which of course are extremely good numbers, with the lower end of those prices comparable to the capital cost of combined-cycle natural gas plants today.

I think still the record is Point Beach, which cost less than $1/We inflation adjusted.