The AP1000 Loan Debacle

Freeze regulation, not technology.

Figure 1. Oconee. Maybe the best nuclear plant ever. It was not built by Westinghouse.

With the Westinghouse loan, the Trump Administration has invented a new form of state capitalism, an oxymoron if there ever was one. And it will bury US nuclear in an even more expensive coffin.

Details are almost non-existent. Here’s my limited and quite possibly erroneous understanding of the deal.

1) In exchange for an unspecified amount of tariff relief, Japan will buy $550 billion dollars of ultra-long US bonds, almost certainly a terrible investment as the US inflates away the value of that paper. Japan is either betting that it can get that money back in trade, or this is the price of the US military umbrella. Either way the US taxpayer will end up with the bulk of the bill.

2) Trump will take 80 billion of that public money and loan it to Westinghouse to build “up to” eight AP1000’s. If the resulting monopoly is a success, the government can convert the debt into a one-sixth share of Westinghouse.

It’s hard to imagine a worst plan. It will strangle competition while exacerbating the real problem.

Strangle Competition

Imagine how you feel if your GE-Hitachi or the other outfits that have NRC certified designs. You’ve spent 100’s of millions fighting your way through all the NRC barriers to entry; and now the US government turns on you and finances your main remaining competitor with taxpayer money. Probably best to concentrate on the Japanese market.

The position for the newcomers is even worse. The taxpayer has already blown over 700 million on NuScale. Do they now have to spend more to defend this investment against themselves?

The Terrapower’s et al who don’t yet have a license can forget about any more private investment. The whole point of blowing all the money and time on getting a license was to obtain a monopoly which would allow you to fleece the rate payer. Now all it gets you is a chance to compete with a lavishly taxpayer funded, partially owned by your regulator.

The only real hope for the US was the Koreans showing the way with the APR1400. Whatever chance we had of the Koreans entering the US market, just disappeared. ALARA-based regulatory uncertainty was bad enough, but now that regulatory weapon is wielded by a publicly funded competitor.

Exacerbating the real problem

US nuclear’s real problem is a tragically misdirected hopelessly unbalanced, dictatorial regulatory system from which there is no appeal. With this loan, the Trump administration is admitting that it is not going to change that system in any substantial manner. Much worse, now that the federal government coffers are open, nuclear, actually Westinghouse, becomes rather like the US Navy. The ALARA-based regulatory cost limit is no longer the cost of the low CO2 competition, wind and solar, which limit was already nearly non-existent, given the cost of trying to make W/S dispatchable. Rather it is the taxpayer’s ability to avoid being fleeced. In the Navy’s case, that ability is so weak that the ships’ did-cost is 20 and 30 times their should-cost, and the ships don’t work.

The NRC was always hampered by the fact that, if they made nuclear too expensive they would not have any customers. But now that Westinghouse can tap into public funds that annoyance disappears. US nuclear’s did-cost will explode.

The Standardization Argument

The AP1000 loan will be defended on the grounds that the solution is standardization. That’s rubbish.

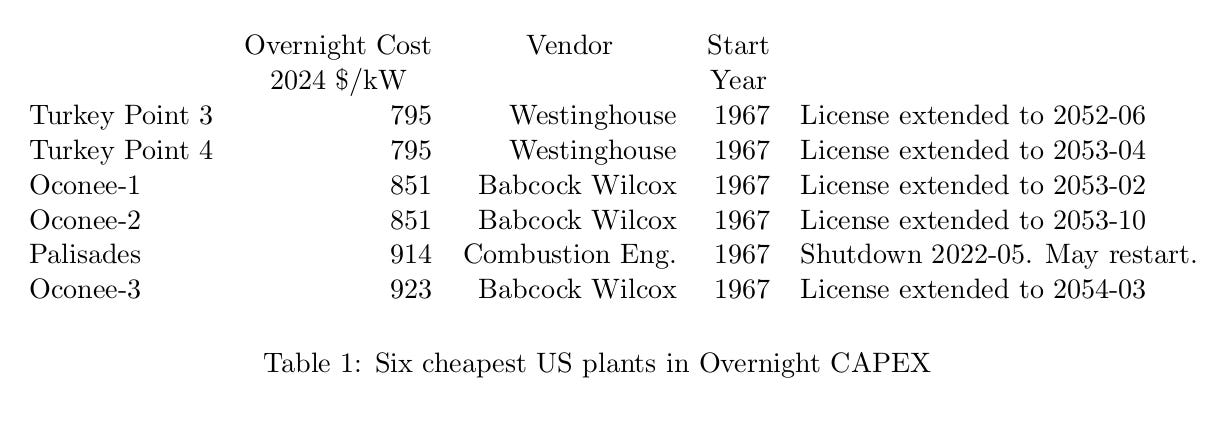

The US’s first full scale plants in the mid-late-1960’s were the cheapest nuclear plants ever built. Six of those plants came in at an overnight cost of less than $1000 per kW in today’s money, Table 1. At the time we had four major vendors (B&W, Combustion Engineering, GE, and Westinghouse) fighting for the market combined with a regulator that was still more promotional then preventional. Basically, the vendors self-regulated. As the vendors gained experience from building more and more plants in the early 1970’s, the costs skyrocketed.

Oh, but that’s because the industry didn’t standardize. The stupid vendors kept changing their design. If they hadn’t done that, everything would have been fine. Nonsense. Voluntary fixes and improvements don’t increase costs or build times. They decrease them.

As a very young technology, the nuclear vendors should have learned from each build and applied that new knowledge to the next job. Not to mention the rapid improvements in materials and engineering design thanks in part to the computer during the early second half of the 20th century. The real cost of nuclear should have fallen significantly during this period as these improvements were adopted.

The problem was not voluntary improvements, but rather the involuntary changes forced on the vendors by regulatory volatility and uncertainty. A 1974 study by the General Accountability Office of the Sequoyah plant documented 23 changes ``where a structure or component had to be torn out and rebuilt or added because of required changes.”\cite{ford-1982}[p 208] The Sequoyah plant began construction in 1968, with a scheduled completion date of 1973 at a cost of $300 million. It actually went into operation in 1981 and cost $1700 million. This was a typical experience.

By 1978, the NRC was really rolling. The apparat was pumping out 1.3 new regulatory requirements on average every working day.\cite{smil-2010}[p 36] Just about every one of those new rules made something in the existing designs illegal. To make matters much worse, even the tiniest change started a time-consuming flood of paperwork.

In 2009, the NRC imposed a new aircraft impact rule on the already designed AP1000 which forced changes all the way down to the foundation. According to one NRC official, the massive redesign and reapproval was Westinghouse’s fault because they should have foreseen that this requirement was coming. The NRC turned design into a guessing game.

Lack of standardization is indeed a real problem for US nuclear. But it is the regulation that need standardization; not the designs. The Westinghouse loan not only does nothing to standardize regulation, but instead it makes things much worse by allowing the regulator to impose even more expensive requirements.

The AP1000 Choice

If you want a concrete argument why we should not standardize on a single design, look no further than the AP1000. The AP1000 is a cramped, nearly unmaintainable, crappy design. The design philosophy appears to have been to minimize up front CAPEX subject to meeting NRC paperwork requirements. On paper, the AP1000 has a design life of 60 years. Westinghouse knows better. They gave Georgia Power a warranty period of 2 years starting from the date of Substantial Completion, with a cap of 10% of the contract price. You will get a better guarantee with a toaster.

So US nuclear is now a monopoly based on a lousy standardized design using a klunky, brute force technology, regulated by an unstandardized autocracy who can now tap public funds to pay for its whims. It’s hard to imagine that it can get worse.

Trump doesn’t understand economics, what’s new. Biden was not much better with the IRA. Nuclear will thrive if the regulatory stranglehold is removed and carbon is priced to match its impact. Unfortunately I can’t see it happening, but on the positive side the need is so great that I am sure Terrapower and some of the other innovators will find a market.

There are so many missing details. My understanding, which is almost certainly incomplete and partially wrong, is as follows: I wrote about this a few weeks ago.

Under Trump's Japan "trade deal," the US and Japan agreed to economic cooperation.

1) The US will select projects if $1 billion or more through the recently created "Economic Accelerator." Basically, a panel picks and chooses infrastructure projects and uses every lever available to expedite permits.

2) The US asks Japan to fund it through government-sponsored banks or loan guarantees (exactly how I am unclear).

3) If the Japanese side agrees, they must transfer the money or support within 45 business days. The US sets up a Special Investment Vehicle to receive the funds, and Japanese vendors get priority for related contracts.

4) Once complete, the Japanese get 50 percent of the after-tax cash flow of the investment vehicle until the loan is repaid, with interest. Then, the Japanese still get 10 percent of cash flows in perpetuity.

While interesting, it also doesn't sound very "America first" when you think about it. Japanese firms are getting contracts, they are getting loans repaid, with interest, and continued cash flows even after the loan terms are satisfied.