What if tanker crew deaths are intolerable?

Figure 1. Big whiteship, 500,000 tons on the move. Built in 12 months in 2002 at a cost of 89 million USD. The two little orange dots near the stern are 50 man lifeboats.

World class commercial shipyards, exposed to a brutally competitive market, have developed truly remarkable productivity. I have watched this magic. Flat plate comes in at one end of the property and an immense, complex ship goes out the other end. A good yard needs only 400,000 man-hours to build a tanker weighing 30,000 tons empty, a little more than 10 man-hours per ton. This includes everything: coating, piping, wiring, machinery, and testing. The contract is fixed price, which will be about $3000 per ton. The ship will be built in less than a year. The ship must perform per contract and there are substantial penalties for late delivery.

A good shipyard needs about 5 man-hours to cut, weld, coat, and erect a ton of hull steel. The yards achieve this remarkable productivity by block construction. Sub-assemblies are produced on a panel line, and combined into fully coated blocks with piping, wiring, HVAC (and scaffolding if required) pre-installed. In the last step, super-blocks, weighing as much as 3000 tons, are dropped into place in an immense building dock.

The whole process is carefully choreographed. The yards do their own detailed design, which has to carefully match their production process, including their man-power levels by trade. Every operation including each crane lift is scheduled down to shift level. The scheduling is so tight that a hang up anywhere in the yard impacts all the other projects in the yard.

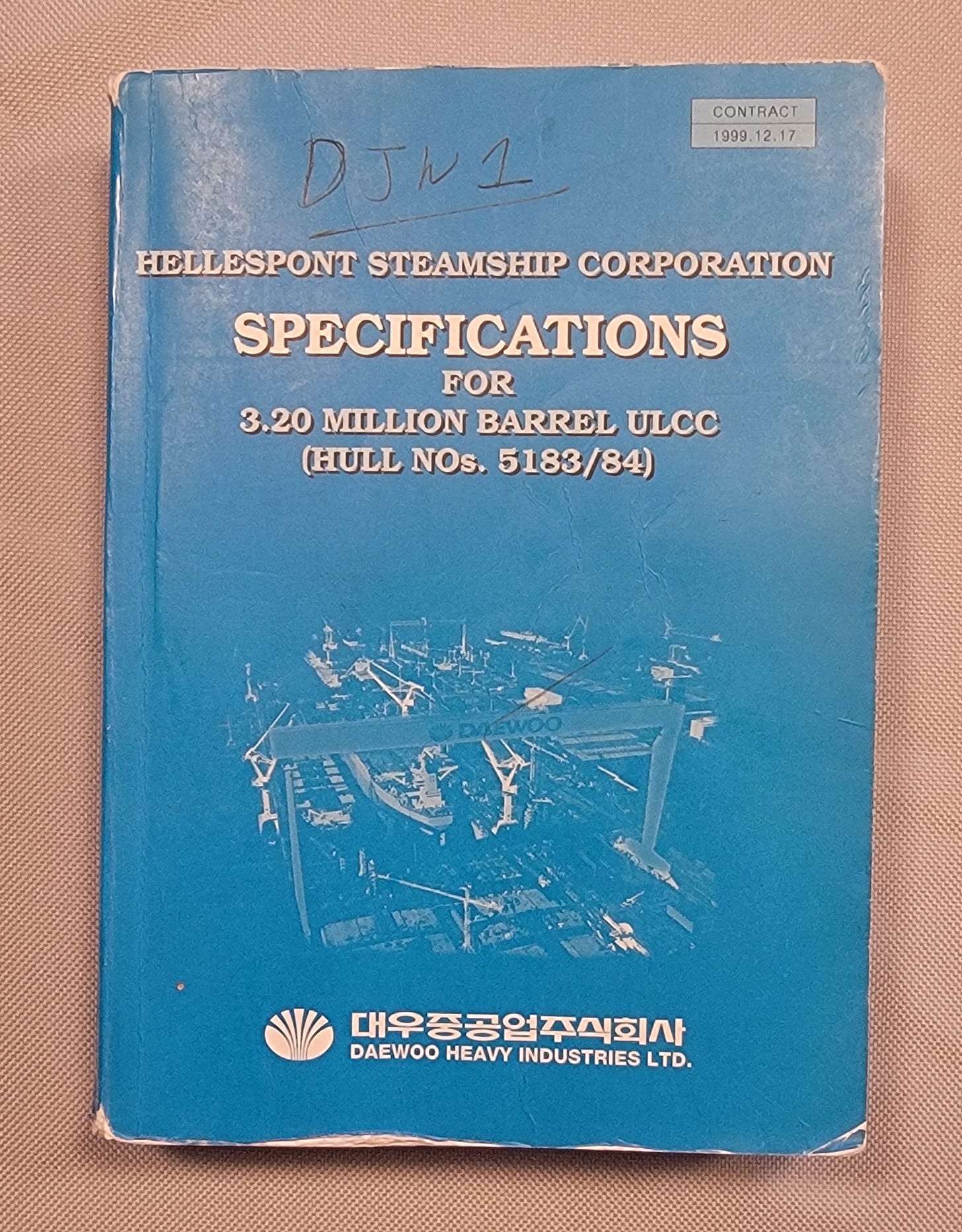

Figure 2. My copy of the Big Whiteship Spec

What is controlling this complex process? It all starts with the Specifications, almost always shortened to the Spec. In the case of the ship in Figure 1. the Spec was a 366 page document, Figure 2, which lays out the ship’s operational requirements, the tests that will be undertaken, and the rules that must be followed. The Spec incorporates 40 or more other codes and sets of rules by reference. Each of these references in turn may reference many other codes and rules.

The Spec is functional in nature. It delineates what the ship must do, what tests each component must undergo and pass, during the construction process. It outlines the sea trials in considerable detail. But it rarely dictates how a component will be built. And it spends almost no time on paperwork requirements.

The Spec is hammered out in week long negotiations between the yard and the shipowner. Each side will have a team of at least 3 or 4 people at the table. They go through the Spec line by line, and haggle over the wording. They know every adjective counts. Once each page is agreed, it is initialed by the lead of each team.

In the shipbuilding business, the owner's inspectors are called superintendents. We had our specs printed up as 5 by 7 inch booklets. Each of our superintendents carried a copy whenever he was involved in an inspection. Most of the superintendents committed portions of the Spec to memory. Superintendents can witness all the tests and can reject any results that do not meet Spec requirements. They must be given adequate notification; but, if they don't show up on time, the test is deemed passed.

If a superintendent was unhappy with anything, he would whip out the Spec, point to the relevant clause, and ask for a correction. Usually the yard guy on the spot would comply, rather than risk a hold up in production. But if he thought the superintendent was asking for something that was not in the Spec, and they can't reach an agreement, the issue would be bucked up to the next level, and in rare cases all the way up to yard and owner top management. If the situation was still unresolved, they would have to go to arbitration; but this never happened in my four years in Korea.

The point is the rules are clear; everybody knows the rules. The yard tries to bend the rules to the low side; the superintendents try to push the rules to the high side. But the rules are the rules; and everybody has to stick to them. If the Spec is well written, the result is a quality ship, built on time at a remarkably low price.

Now suppose we bring a third party into this astonishingly productive system. Society has decreed that the death of a seaman is intolerable. So we have set up the Ocean Safety Directorate (OSD). The OSD's job is seaman safety. The OSD gets no credit for all the economic benefits associated with cheap ocean transportation. But if a single crew member is lost at sea, the OSD will have failed at its job, and its employees will suffer the consequences.

The OSD is not only empowered by law to write the rules for shipbuilding, but also has been given the unilateral authority to change the rules when it sees fit. The rules don't even have to be rules. They can be amorphous goals such as "safe as reasonably achievable". But the OSD inspectors get to decide what such aspirations mean in any particular situation. Nobody is sure what the rules are. Designers have to guess what the rules will be and how they will be interpreted.

OSD employees will note that many of the stairs are little more than ladders, steep and narrow. Falls could be deadly. They will see that there is no protection from snap back if a mooring wire parts under tension. It is possible for a person to squeeze through railings. It would be easy to climb over them. There is no fully protected way for crew to move from the stern to the bow. People could be washed overboard in bad weather. The engine room is full of dangers. Access to hot or moving machinery is not completely prevented. Single wall, high pressure steam lines have no secondary protection. They will move swiftly to correct these failings.

But they know no matter what they do, they cannot prevent all seamen deaths. So they must devise a way to show that, when that catastrophe happens, they have done everything they could to prevent it. They require detailed analyses showing that any possible mistake or failure by man or machine will not result in a seaman death.

They require that all vendors go through an expensive and restrictive certification process. The yard is no longer free to bid anyone it wants to. Newcomers need not apply. The incumbent vendors enjoy a deep regulatory moat. Their focus becomes maintaining the paperwork required to preserve that moat. Cost is determined by amount of paperwork not quality.

The OSD writes detailed process requirements dictating just how components will be manufactured and who can do that work. They imposes multiple layers of paperwork documenting that all their procedures have been followed. Any change has to go through a long list of sign offs, requiring reanalysis of anything that might be affected. How long these approvals will take is anybody's guess.

They instruct their inspectors to reject any departure from an approved drawing no matter how trivial or beneficial. If an OSD inspector does not show up for a required test, the test has to wait until he does.

What do you think will happen to our shipyard's productivity? I can tell you what will happen. The carefully choreographed system will be thrown into chaos, and grind to a virtual halt. Cost will increase by an order of magnitude or more. Quality will deteriorate drastically. The ships will be delivered years late. They will rarely perform to spec, some will not perform at all.

Why can I tell you what will happen? US naval shipyards resemble Korean yards on the surface but they are controlled by something that looks very much like the OSD system. In fact, the OSD system is modeled on the Navy system. I spent the first decade or so of my career, working within this system. I saw the focus on process rather than substance. I saw the waste. I saw inexplicable decisions go unchallenged. I saw obvious errors turned into profit centers. I saw promotions based not on output, but on keeping the paperwork clean. I saw horribly bloated initial prices followed by enormous overruns. I saw schedules busted by months and then by years. I saw ships that did not work. I saw everybody involved stridently defend the system.

Thank God the OSD does not run nuclear power. We'd have no chance of solving the Gordian Knot.

Whenever I read about how other industries are working I am left in awe of how much nuclear is still in its infancy with regards to all the obvious efficiency gains that we still have to get. Really shamefull for a 60 year old industry, but no wonder with all the incentives making all the innovation go into coming up with more integrit paperwork instead of delivering a competetive product.

I feel with the tanker an oil spill is a more accurate analogy since it is the effect on the public not the operator that is the main concern and the proposed system of underwriter insurance is reasonably close to how maritime insurance aligns incentives for their industry

If shipbuilding was run by government (directly or through heavy regulation as you lay out), the Spec handbooks would consist of 190,000 pages and ships would take 20 years to build and cost a trillion dollars.

The info you provided on how building happens is fascinating. It's impressive. It reminds me of reading the details of how semiconductor factories work. They have to go to much greater extremes.