Where did the turnkey contracts go?

The Cost of Regulatory Risk

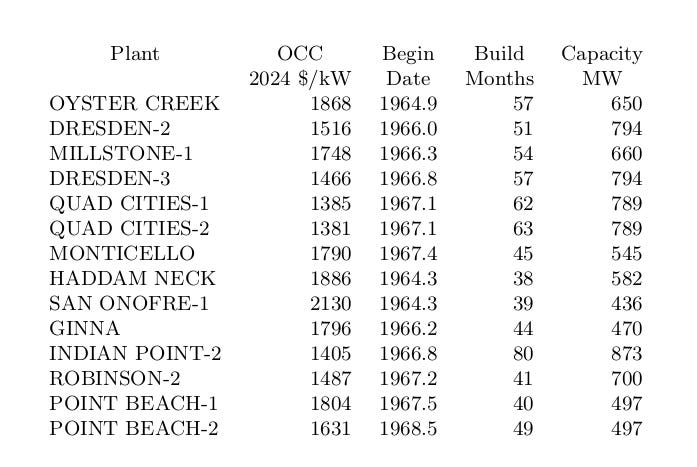

Table 1. Overnight Capital Cost (OCC) of USA Turnkey Plants.\cite{lovering-2016} Only one of these plants came in at over $2000/kW in today's money.

The single most valuable data resource on nuclear power we have is Lovering, Yip and Nordhaus. Historical construction cost of global nuclear power reactors, Energy Policy 91 (2016) 371-382. This paper is a methodical attempt to collect the construction cost of as many nuclear plants as the authors could, and convert these numbers to Overnight CAPEX by stripping out the interest expense. They also collected data on build times.

The Gordian Knot Group has spent a great deal of time pouring over their results, as anybody who is seriously interested in solving the Gordian Knot should. One important conclusion, backed up by other sources, is in the late 1960's nuclear could produce electricity as cheaply as coal when coal was as cheap as it ever was in real terms. Even the staunchest anti-nuke had to grudgingly admit this. Here's Ehrlich griping in 1970

Contrary to widely held belief, nuclear power is not now `dirt cheap'. ... At best, both [nuclear and coal] produce power for approximately 4-5 mills per kilowatt-hour."\cite{ehrlich-1970}[p 57]

This was an astonishing achievement for a nascent technology that did not exist 20 years earlier going up against a 200 year old leviathan. But the new guy had an unbeatable advantage. Coal needed to burn 100,000 times as much fuel as nuclear to produce the same amount of electricity, To make matter worse, nuclear could burn its fuel in a far more compact boiler. And to top it off, nuclear needed none of the pollution control paraphernalia that makes up close to half coal's CAPEX. It was a totally unfair fight.

Coal was doomed. Not only was it a mature technology which meant that nuclear's real cost would further decline faster than coal's as each technology advanced; but even worse coal was facing a whole new set of pollution regs which would end up close to doubling its real cost. Coal was toast.

And the smart money knew it. In the 1960's, some of the smartest money was controlled by Big Oil. The Oil Patch competitive culture breeds a different sort of executive, less risk averse, and more willing to think outside of the box. These guys could see what was going to happen to coal so they jumped on the nuclear bandwagon big time. These hard-nosed, common sense, Greatest Generation engineers, could not comprehend what the Two Lies would do to nuclear. They took a big hit when nuclear flopped.

The Lovering data base identifies the US plants that were built with turnkey contracts. Table 1 lists those plants and their Overnight Capital Cost (OCC) per kW capacity. There are 14 plants, all of which began construction between 1965 and 1968. The contracts would have been signed well before this date. In compiling their OCC's, Lovering et al attempted to estimate the actual capital cost of the plant, not the contract price. Early on the nuclear vendors were willing to take a hit on the contract in order to lock in a highly profitable fuel contract. For example, the contract price of the 650 MW Oyster Creek BWR was $60 million dollars. Anti-nukes such as Daniel Ford have claimed that GE's actual CAPEX was "as much as 90 million".\cite{ford-1982} Lovering et al appear to have used the latter figure for their database.

The question on the table is: why were there no turnkey contracts after 1968? The nuclear vendors also built coal plants, and they continued to be fixed priced contracts. The vendor who builds scores of plants is in a far better position than a utility to manage the construction. The utilities know that and, far more importantly, they know that, if they accept anything other than fixed price, the vendor's incentive all of a sudden changes from getting the plant built on schedule and on budget to milking the project for as a much money as possible. That's why the utilities insist on fixed price for their coal plants.

What happened? Fixed price contracts can only exist in an environment where everybody knows the rules, and nobody can change the rules after the contract is signed. By 1968, it was clear that the AEC was not prepared to play the game this way. Under Section 187 of the Atomic Energy Act, Congress has empowered the AEC to change the rules whenever it wanted to. and AEC was not shy in taking advantage of this power.

In a competitive market, nuclear would have been dead, defunct, despite its enormous advantages over coal.1 But the utilities were not facing a competitive market. They lived in a market where they could pass on any cost increase as long as they could convince the state regulator that there was no better option. But that could only happen if the utility bore the cost of any regulatory changes. With a fixed cost contract, this was not the case. The turnkey contract, with all its right incentives, had to go.

Now the limit was the cost of coal. As long as the utility could convince the state regulator that nuclear was no more expensive than coal, the regulator had to approve the rates that were required to pay for nuclear. After that, the regulator had to approve any additional rate increases required to pay for new changes in regulation or write off all the already spent money.

What happened next was inevitable. Instead of nuclear's and coal's cost diverging as coal regs tightened and nuclear matured, nuclear's cost rose in lock step with coal's. Bupp and Derian's Light Water is the standard history of early nuclear. These authors note in some wonderment;

Coal seemed to be just competitive with nuclear power from light water reactors at about 25 to 30 cents/mbtu in 1970; it still seems to be competitive at about four times that price in 1976.\cite{bupp-1978}[page 97] [Emphasis in the original.]

Bupp and Derian need not have been surprised. That's exactly what must happen under ALARA based regulation.

Progress depends on a fixed, transparent set of rules. No firm rules, no progress. Two recent examples,

1) Vogtle 3/4. Westinghouse thought it had a fixed set of rules, and signed a fixed cost contract. The NRC changed the aircraft impact rule. Westinghouse went bankrupt. Far, far worse, Georgians are paying 5 times more for their electricity than they should.

2) KEPCO has dropped out of the bidding of at least two West European nuclear projects despite having shown it can build plants at less than half the cost of its US and European competitors.

Dukovany II is an exception that proves the rule. In an environment with little regulatory risk, KEPCO is able to build nuclear plants for less than $4000/kW. KEPCO signed a fixed cost contract with the Czechs; but to insure itself against EU rule changes, it demanded and received a price of $9300/kW. The difference is KEPCO's estimate of the cost of regulatory uncertainty. It will be interesting to see how this gamble works out. I don't normally bet against the Koreans, but I don't like their chances on this one.

We must have a regulatory system, where all the players can be confident that the rules won't change while the game is being played. UCert is such a system. But UCert does have a safety valve. Suppose that we suddenly discover a previously unrecognized risk. A plant's underwriter can require the imposition of a new requirement to counter this risk; but only if all the other insurers would impose the same new requirement. Otherwise the plant would simply change insurer. In such a situation, all plants would have to make the change. The nuclear vendors can live with this safety valve.

With a no-firm-rules regulatory system, the only way nuclear can survive is in a monopolistic market in which the cost of regulatory uncertainty is passed on to the rate payer, or in a subsidized market in which the cost of regulatory uncertainty is passed on to the taxpayer. The latter will have to be the American model in most of the country,

Wow, I didn't realize the Lovering turnkey prices weren't the contract but landed costs. I occasionally see the comment that they were taking losses to compete for market share. That is spectacular

Jack - Great article. You’ve clearly stated some of the actions that led to the outcome of ever rising prices for nuclear power plants and the power they produce.

But the nuclear plant vendors were not the only beneficiaries of rising nuclear plant scope and prices.

The “coal boys”, led Joseph Moody and the National Coal Policy Conference (NCPC) that he directed, worked tirelessly from the late 1950s and into the 1970s to defend their shrining markets from the growing competitive threat from nuclear fission energy.

They did whatever they could think of to damage nuclear’s public standing and to add costs to the enterprise. They had long experience with the costs of adding pollution controls and other regulatory burdens so they figured out ways to push regulators to impose similarly structured burdens on nuclear, even if its “pollution” and “environmental impacts” were far less visible and, in some cases, mostly a figment of creative imagination.

Here’s an old post with additional details.

https://atomicinsights.com/smoking-gun-antinuclear-talking-points-coined-coal-interests/